What is a Cash Flow Statement?

Cash flow means movement of cash. Therefore, Cash Flow Statement is a report that shows the company’s movement of cash over a period of time. It tracks the amount of actual cash coming into and going out of the company’s pockets. These cash can be physical cash that we can touch, like dollar bills and coins. It can also be digital cash like deposits in the banks. Both are cash. The Cash Flow Statement tracks where these cash is coming from and where they’re going.

Along with the Income Statement and Balance Sheet, Cash Flow Statement is one of the three main financial statements. In fact, it’s arguably the most important among the three because cash flow is the key driver of valuation. Ultimately, how much a company is worth is based on how much cash it’ll generate. Cash is also what the company uses to pay for its operations and the key determinant of financial health. If we can only have one financial statement to evaluate a company, we would pick the Cash Flow Statement. You must understand cash flow if you want to get one of the high paying finance jobs.

You can think of the Cash Flow Statement as a financial report that tracks all the cash movements. It adds up all the cash inflows and subtracts all the cash outflows. What we have at the end is the overall net change in cash and the ending cash balance.

Cash Flow Statement Purpose

Different people use Cash Flow Statement for different purposes. Senior management uses it to gauge whether there’s enough cash to pay expenses (i.e. suppliers, employees, etc). Investors use it to analyze the company’s free cash flow profile and value the company. Specifically, credit investors focus on whether the company has enough cash to repay debt with interest. Meanwhile, equity investors focus on the ability for the cash to grow over time. Both groups of investors would also want to use the cash flow to estimate the company’s valuation. Competitors might use it to gain insights into the business and compare the performance with their own.

Cash Flow Statement Example

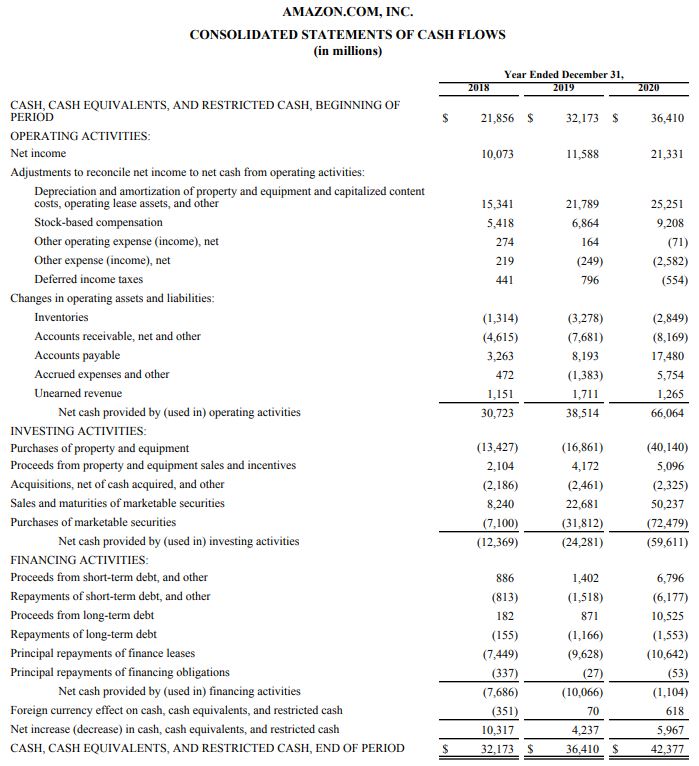

Here’s a real Cash Flow Statement example for Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN). You can find the Cash Flow Statement on PDF page 44 of Amazon’s annual report.

Cash Flow Statement is also commonly known as the “Statement of Cash Flows”. Large companies would often call it “Statement of Cash Flows” on official documents, especially in company reports.

Cash Flow Statement Format

The Cash Flow Statement has 3 sections: Cash Flow from Operations, Cash Flow from Investing, and Cash Flow from Financing. It’s nearly always presented in this exact order. At the end, it adds up all the cash flows to show the overall Net Change in Cash.

Cash Flow from Operations represents the cash flow generated from and used for running the business operations. It includes cash received from customers, cash paid to suppliers, cash paid for taxes, etc.

Cash Flow from Investing represents the cash flow generated from and used for investments. The cash the company use to reinvest into the business to fund expansions, for example, is captured here. Examples include cash used to build new factories, open new stores, buying other businesses and buying stocks and bonds.

Cash Flow from Financing represents the cash flow generated from and returned to investors. The cash the company raises from investors by issuing stocks and borrowing debt are the two primary cash inflows. Conversely, the cash the company uses to pay dividends, repurchase shares, and repay debt are the three primary cash outflows.

The statement breaks out all the key line items within each section. Cash inflows are presented as positive numbers. Cash outflows are presented as negative numbers in parenthesis format. This way, readers can easily distinguish between cash inflows and cash outflows. If you see a number in parenthesis () on the Cash Flow Statement, it means it’s a cash outflow.

At the end, it sums up all the cash flows in these sections to calculate the Net Change in Cash. This represents how much the company’s cash balance has changed over the period of the Cash Flow Statement. Adding the Net Change in Cash to the beginning cash balance would give us the ending cash balance.

[Beginning Cash + Net Change in Cash = Ending Cash]Cash Flow from Operations

Let’s go over the common line items under Cash Flow from Operations. There’ll be variations among companies. Some companies will have more lines, while others will have less. However, the lines below are often the main ones.

Net Income

Under US GAAP, Cash Flow from Operations start with Net Income. Net Income is the first line under Cash Flow from Operations and comes from the Income Statement. It represents the overall profit of the entire company. It adds up all the incomes (Revenue, interest income, other incomes) and subtracts all expenses (operating expenses, interest, taxes). This is the ultimate amount of profit that the company earned for shareholders during the period.

Depreciation & Amortization (D&A)

Depreciation & Amortization is an expense that reflects the usage of the company’s assets. As the company’s assets are used over time, they experience natural wear and tear. D&A is an expense that captures this natural wear and tear. The Income Statement subtracts D&A expense to calculate Net Income. However, there’s no cash payment required for D&A. No cash is paid for ongoing wear and tear. D&A is merely a reflection of reduction in asset value as assets are used up over time. Therefore, D&A is a non-cash expense. Because it’s deducted in Net Income, we need to add it back here to neutralize the impact of the non-cash expense.

Stock-Based Compensation (SBC)

Stock-Based Compensation is an expense that reflects the portion of the company’s compensation expense paid with stocks as opposed to cash. SBC is part of the total compensation expense, which is usually part of the SG&A expense. The Income Statement subtracts the entire SG&A expense to calculate Net Income, which means it also subtracts SBC. However, SBC is a non-cash expense. No cash was paid because the company paid with stocks instead. Therefore, it’s a non-cash expense and we need to add it back.

Changes in Accounts Receivables

When Accounts Receivables decrease, it means the company has collected a portion of the outstanding payments from its customers. Therefore, it’s a cash inflow. When Accounts Receivables increase, it means the company hasn’t collected payment on a portion of the period’s revenue. As a result, the amount of increase in Accounts Receivables must be deducted from Net Income because that’s not cash. That’s why Changes in Accounts Receivables impact Cash Flow from Operations.

Changes in Inventory

When Inventory decrease, the difference adds to the company’s cash flow. When inventory increase, the change decreases the company’s cash flow.

Changes in Accrued Expenses

Accrued Expenses are unpaid expenses that the company has accumulated over time. When Accrued Expenses increase, it means there are more unpaid expenses. This means a portion of the expenses deducted in the period’s Net Income hasn’t been paid with cash yet. However, Net Income had subtracted the entire expense regardless of whether it’s paid or not. To give credit to these unpaid expenses that were subtracted, we add increases in Accrued Expenses to cash flow.

Likewise, when Accrued Expenses decrease, it means the company used cash to pay off the accumulated unpaid expenses. That’s a use of cash. Cash is moving out of the company. Therefore, we subtract the decrease in Accrued Expenses from Net Income to calculate Cash Flow from Operations.

Changes in Prepaid Expenses

Prepaid Expenses is the value of the cash payment made in advance for expenses, before they are incurred. It’s the amount of cash the company has paid upfront for future expenses. For example, suppose a company pays $10,000 in advance for next year’s insurance. The $10,000 is a Prepaid Expense. Logically, an increase in Prepaid Expenses means the company has spent more cash. It’s a cash outflow, so we need to subtract it from Net Income.

Likewise, a decrease in Prepaid Expenses means the company had incurred expenses that it had already paid for. These expenses are subtracted in this period’s Net Income. But because these expenses had already been paid for, they don’t require cash payments in the period they are incurred. In other words, there were no cash outflow associated with these expenses incurred during the period. Therefore, we add decreases in Prepaid Expenses to Net Income to give credit to these prepaid expenses.

Cash Flow from Investing

As a reminder, Cash Flow from Investing represents the cash flow generated from and used for investment activities. Generally speaking, there are three types of investments. The first is physical assets, known as Property, Plant & Equipment or PP&E for short. It includes things like factories, office buildings, chairs, tables, refrigerators, computers, etc. The second type is businesses. If a company were to spend cash to acquire another business, the cash being spent is an investment. And the third type is securities, like treasuries, stocks and bonds. Securities are investments the company makes to earn some extra cash on the side.

Capital Expenditures

Capital Expenditures (CapEx) is the cash spent on Property, Plant & Equipment (PP&E). You can think of CapEx as the cash used to purchase physical assets. If a company were to spend $20,000 buying a new machinery for its factory, that $20,000 is a CapEx. CapEx is a cash outflow. It’s a usage of cash that usually brings Cash Flow from Investing down to the negative territory.

Proceeds from Sale of PP&E

Proceeds from Sale of PP&E is the cash received from selling the company’s physical assets. It’s exactly what the name sounds like. This line is the polar opposite of Capital Expenditures. Whereas CapEx represents cash spent on buying physical assets, this line represents the cash received from selling existing physical assets. This is a positive number on the statement because it’s a cash inflow.

Acquisitions, Net of Cash Acquired

This is the amount of cash spent acquiring other businesses, net of the cash that comes with the acquired business. Whereas CapEx is purchases of physical assets (i.e. chairs), Acquisitions refer to the purchase of entire companies (i.e. LLC, corporations). This is cash being spent, so it’s a cash outflow.

Purchases and Sale of Marketable Securities

Marketable Securities are investment instruments that can be easily bought or sold. Examples are treasuries, stocks and bonds. Purchases of Marketable Securities are cash used to buy these securities. Companies may have a lot of cash in the bank. They want to put these cash to good use and earn some extra money on the side. Purchases are cash outflows, so they show up as negative numbers.

In contrast, Sale of Marketable Securities refers to the cash received from selling the investment instruments the company owns. It’s the cash proceeds received from selling the company’s investment portfolio of treasuries, stocks and bonds. The cash proceeds received are cash inflows, so they show up as positive numbers.

Cash Flow from Financing

Cash Flow from Financing captures the cash movements between the company and its investors. Inflows are cash the company receive from investors whereas outflows are cash the company returns to investors. Credit and equity investors are the two main types of investors in a company. Therefore, the financing line items mainly relate to cash movements between the company and its debt and equity investors.

Proceeds from Debt Issuance

Proceeds from Debt Issuance are cash received from borrowing debt. The company is raising money to fund its operations by issuing debt. “Issuing debt” is just a fancy term for borrowing debt. The company is receiving cash from lenders. Therefore, it’s a cash inflow and shown as a positive number on the statement.

Repayment of Debt

Repayment of Debt is the cash used to repay debt. The company is taking money out of its bank accounts and paying back the debt it had borrowed. However, note that the value in this line only refers to the repayment of debt principal. It does not include Interest Expense, which is included in Net Income under US GAAP. It’s a cash outflow and shown as a negative number on the statement.

Proceeds from Stock Issuance

Proceeds from Stock Issuance are cash received from issuing additional shares to investors. The company is raising money by giving a piece of the company to investors who provide cash. In other words, it dilutes existing shareholders’ ownership stakes in the company. After the stock issuance, the company has more cash but the existing owners own a smaller proportion of the company. It’s a cash inflow and shown as a positive number on the statement.

Dividend Payments

Dividend Payments are the cash returned to shareholders from the profits the company has earned. The company is taking cash out of its bank accounts and giving these cash back to its investors. Hence, it’s a cash outflow and shown as a negative number.

Share Repurchase

Share Repurchase is the amount of cash the company spent to repurchase shares. Buying back shares is a common method of returning capital to equity investors. It’s often more tax-efficient than dividend payments. The company is using cash to buy its stocks back from stockholders. Therefore, it’s giving cash back to investors and a cash outflow.

Foreign Currency Effect

The Cash Flow Statements of large, multi-national companies often have an additional line at the bottom called Foreign Currency Effect. What is this line and why do companies have it?

To understand this line, we need to understand the cash holdings of large multi-national companies. These companies operate in many different countries with different currencies and bank accounts. They’ll have some cash in each country denominated in the local currency. Logically, they need to have cash in local currency in order to fund their local operations. For example, they need to pay employees in Europe with Euros and employees in Japan with Yen. Therefore, multi-national companies spread their cash balance across many different currencies. However, for the purpose of the financial statements, companies have to present their total cash balance in a single currency. They have to account for the cash held in many different currencies in a single currency. Therefore, they have to convert different currencies into a single currency to get the total value of the cash balance.

Unfortunately, the foreign exchange rates among currencies don’t stay the same. They fluctuate daily. When foreign exchange rates fluctuate, it impacts the value of the company’s overall cash balance. Therefore, the value of the company’s cash balance would change every day even without any cash flow activities. To capture the impact on cash balance from foreign exchange rate fluctuations, companies have a line called “Foreign Currency Effect”. It captures the impact on cash balance due to foreign exchange rate fluctuations during the period.

Net Change in Cash

At the bottom of the Cash Flow Statement, it shows the Net Change in Cash. Net Change in Cash is the overall change in value between the company’s cash balance at the beginning of the period and its cash balance at the end. We can calculate Net Change in Cash by adding up all the company’s cash flows and the Foreign Currency Effect on Cash.

Income Statement vs. Cash Flow Statement

Why do we need the Cash Flow Statement when we already have the Income Statement? Doesn’t the Income Statement already tell us how much money the company is making?

Recall that while the Income Statement measures the profitability of the company, it does not measure cash flow. Profits and cash flow are two completely different things. Income Statement measures profits. The Cash Flow Statement measures cash flow.

To illustrate how profits and cash flow differ, let’s review how companies record the values on the Income Statement. Companies record the values on the Income Statement under Accrual Principle and Matching Principle.

Accrual Principle requires companies to recognize revenue when products are provided, without regards to whether cash is received. For example, if a business had delivered goods to a customer before getting paid, it has to record revenue nonetheless. Likewise, if a customer has already paid but the business has yet to provide the product, then the company can’t record the transaction as revenue. Therefore, revenue is the value of goods and services delivered to customers. It’s not cash received.

Similarly, companies recognize expenses under the Accrual Principle and the Matching Principle. Those expenses that have a direct relationship with revenue are recorded when their corresponding revenue is recorded. For example, the cost to produce a product is recognized when the revenue from that product is recognized. Expenses that do not have a direct relationship with revenue are recognized in the period they are used. Pay attention to the criteria here. At no point is the expense recognized based on when cash is paid.

Because of these accounting principles, the values on the Income Statement do not represent cash flow. Cash Flow Statement, on the other hand, measures cash movements purely based on cash received and cash paid.

What Does the Cash Flow Statement Tell You?

To financial analysts, the Cash Flow Statement is arguably the most important among the three financial reports. But why? What does the Cash Flow Statement tell you? Here, we’ll lay out some of the most important insights we can get from this statement.

Free Cash Flow Profile

We need the company’s Cash Flow Statement to calculate its free cash flow metrics. Specifically, we care about Levered Free Cash Flow (LFCF) and Unlevered Free Cash Flow (UFCF). Levered Free Cash Flow and Unlevered Free Cash Flow are two highly important metrics in investing. We won’t be able to calculate them without Cash Flow Statement. The amount of free cash flow the company generates drive its valuation. These free cash flow metrics also enable us to determine the company’s ability to spend on certain items. For example, they enable to estimate how much debt a company can repay or how many shares it can repurchase.

Capital Intensity

The Cash Flow Statement tells us the capital intensity of the business. Said differently, it tells us how much capital the business needs to run its operations or expand its footprint. Specifically, we can look at the Capital Expenditures history. Does the business require a lot of CapEx to keep its business up and running? A capital intensive business would require a lot of CapEx. A non-capital intensive business would have very little CapEx.

Acquisition History

You can get a sense of the company’s acquisition history from the line Acquisitions, Net of Cash Acquired. You can see how much the company spent to buy other businesses and when. There are situations where you’ll need to derive the price the company paid to acquire another business. If the company’s press releases don’t disclose the purchase price, then you can get an estimate from the Cash Flow Statement.

You can also triangulate price paid with valuation multiples to back-solve for the target company’s operating metrics. Once you have the operating metrics, you can potentially back them out of the company’s overall operating metrics. This will allow you evaluate the business’s organic performance independent of acquired financials.

Capital Return Programs

Capital return is an important factor for some investors. We can see whether the company is returning capital to shareholders under Cash Flow from Financing. If the company pays dividends, then it’ll show Dividend Payments. If it has a share buyback program, then it’ll show the amount of cash spent on repurchasing shares. Companies that are not returning capital to investors will not have either of these two lines.